22

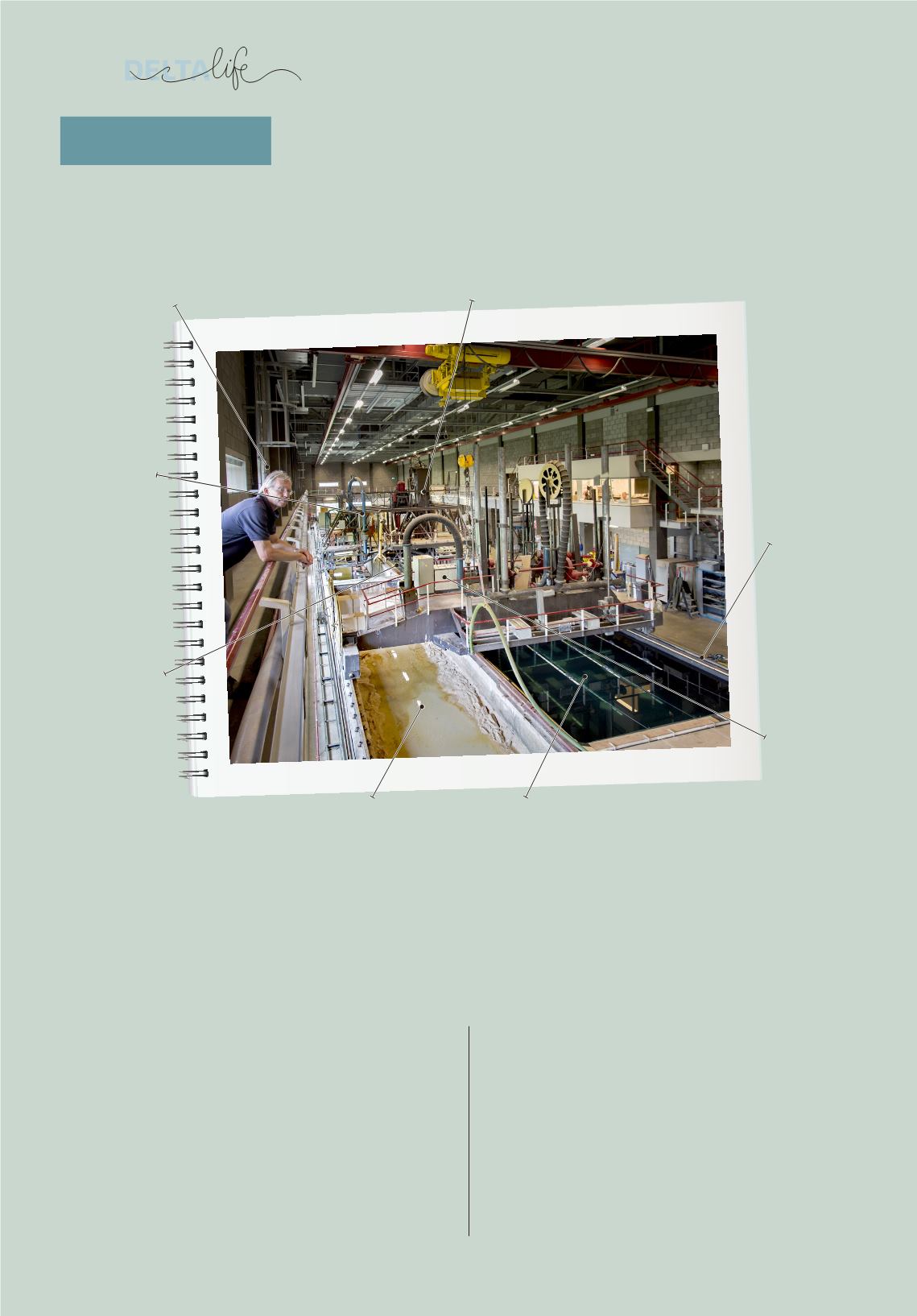

Marcel Grootenboer supervises the physical processes in the Water-Soil Flume.

Marcel Grootenboer

keeps an eye on the

carriage.

Cutter digs into the

sediment, a pump

sucks it up through

a hose.

The 43-tonne carriage moves

along the flume like a professional

dredging plant.

Four electric

motors on each

wheel push the

carriages on rails.

Sediment is dumped

in a chute to be

used again in other

experiments.

Measurement flume: 50 m long,

5.5 m wide and 2.5 m deep;

contains water and soil.

Glass partitions to

adjust the size of the

flume.

Equipment connected

to the conditioning

carriage measures

the physical proper-

ties of soil and water

such as salinity and

soil stability.

The seabed is a working location: it is where we dig for

sand to strengthen the coast, lay power cables and

build wind farms. Offshore engineering involves many

challenges: the stability of the bed and the interaction

between soil and water, for example. Moreover, it is

important to bury cables deep enough to prevent

damage by anchors, and equipment has to be strong

enough.

To conduct the relevant tests, we have the Water-Soil

Flume, the world's largest facility where engineers can

simulate natural processes involving water and soil.

Deltares uses the flume to study new applications:

salt intrusion at locks, injecting bog iron to strengthen

soil, and mining precious metals. We study water with

different salinities and all types of soil: sand, clay or

rock.

The tests help to assess risks, perfect technologies and

make decisions about how strong ships and excavators

need to be. This knowledge is needed by dredgers, ship-

builders and national authorities to make working at sea

better, safer and more economical throughout the world.

MAKINGWORK ON THE SEABED

SAFER AND CHEAPER

TESTING GROUND