14

DOSSIER

LAND SUBSIDENCE

The subsidence of soft soils such as peat is a global problem.

California, Italy and Indonesia have developed their own

ways of dealing with the consequences of land subsidence.

‘Sound science is the only way to convince people.’

BY PJOTR VAN LENTEREN

ITALY, AMERICA AND

INDONESIA STRUGGLE

WITH SOFT SOILS

PHOTO: THINKSTOCK

15

DELTARES, FEBRUARY 2015

F

or anybody who works with agriculture and

homes in peat areas, there is no escaping

the challenges: land subsidence, flood risks

and greenhouse gases. The Italian Po Valley,

Sacramento Delta in California and the coastal

zones of the Indonesian islands are all facing the

same difficulties, but they have adopted different

approaches. How can local scientists get the topic

onto the agenda, how are they trying to counteract

the effects of land subsidence, and what can other

countries learn from them?

Po valley: a fine balance

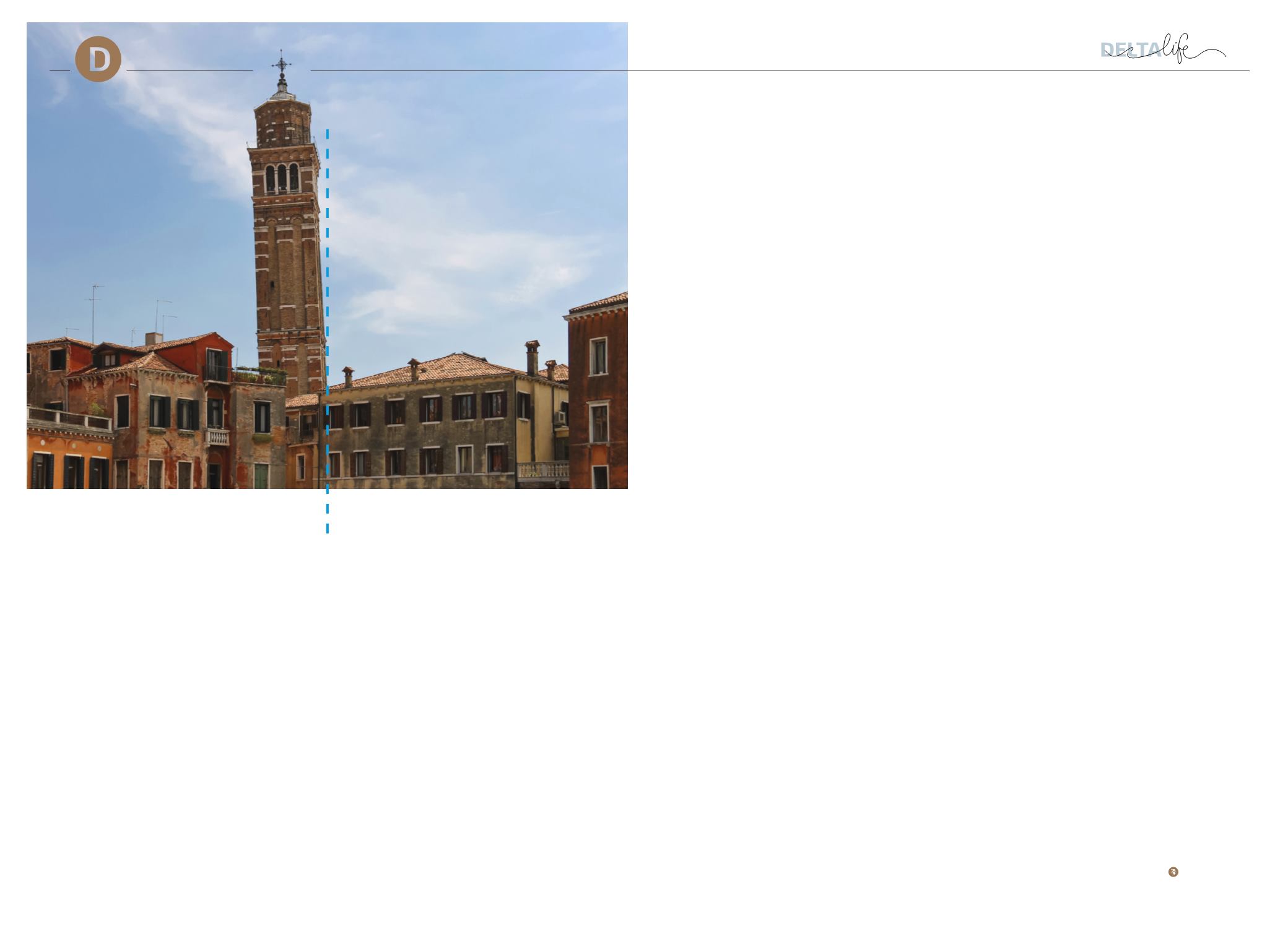

Everyone knows that Venice can just keep its head

above water, but the real problems are found where

tourists don’t go, in the Marghera, the agricultural and

industrial area around the city. Here, the peat ground

is located a number of meters below sea level. Until

the 1970s, this was caused by deep groundwater

being pumped to the surface. After an aqueduct was

installed, land subsidence continued, but now as a

result of the drainage of agricultural land. ‘This type of

subsidence is not as fast, but it is much more difficult

to stop’, argues Pietro Teatini of the University of

Padua. ‘If we pump too much, the land subsides; if we

pump too little, there are floods.’ Water authorities in

the Po valley have to meet the challenge of striking

a fine balance in both natural and political terms. ‘It

has been agreed with farmers to plough 30 cm rather

than 70 cm. That is already an enormous help.’

California: convincing farmers and the

public

In Venice, the problems are easy for all to see; in the

USA, there are areas where it is much more difficult

to convince the government and business about

land subsidence. ‘America is affected by all types of

land subsidence’, explains Devin Galloway of the US

Geological Survey, ‘but the most frequent solution is

to move the problem. There are plenty of uninhabited

areas.’ In the Sacramento Delta near San Francisco,

farms are located on peat islands between busy river

arms. ‘If you stand at the bottom of the bowl, you

look up at sea-going vessels as they sail by.’ Even

here, it hasn’t proven easy to raise awareness of

the problem among local people and farmers: the

farmers themselves live safely on higher land. ‘On top

of that, the economic stakes are considerable: one

third of the USA’s table vegetables are produced here.’

Forward-looking areas are trying to buy out farmers

and submerge the land in question. Sedimentation

creates new land. ‘That sounds good, but the process

is not fast enough and we are struggling with the

salinisation of the groundwater. We do hope it will buy

us time so that we can find better solutions.’

Indonesia: palm oil and paper pulp

Not many people associate the tropical coastal

zones of Indonesia and Malaysia with peat. But that

is precisely what you find below the jungles, three

quarters of which have already been cut down: 25

million hectares, roughly the surface area of Great

Britain. Until the 1990s, the main industry here

was forestry, with the selective felling of sustainable

timber such as meranti. ‘Since they started producing

palm oil and pulp for paper, things have taken a turn

for the worse’, explains Aljosja Hooijer of Deltares.

‘Drainage leads to the loss of peatland and these

areas are now facing more and more floods, with the

country’s emissions of greenhouse gases almost

matching the USA and China.’ Due to the lack of

proper maps showing peat and land levels, it is easy

to question whether the problems are real. At the

moment, environmental organisations and business

are the main actors pushing for more sustainable

approaches, financing research into the loss of

peat and land subsidence, and drawing up accurate

maps using aeroplanes and laser technology. The

data make it possible to predict how fast flooding

will increase, and what can still be done by reducing

drainage. ‘But it continues to be a difficult discussion:

should a company or a government agency pass on

profits that can certainly be made this year for the

sake of more sustainable, but lower, profits in ten

years from now? The only way to convince people is

by doing good science, and producing sound data.’

Land subsidence in areas with soft soil, like those in and around Venice, can, in

combination with poor foundations, result in the subsidence of historic buildings,

as here in the case of the Santa Maria Gloriosa del Frari.