11

10

DELTARES, FEBRUARI 2015

DOSSIER

LAND SUBSIDENCE

Damage to housing and infrastructure,

flooding. Government authorities put a lot of

money into addressing these challenges. At

least, that is what they believe. In fact, many

of them are still not aware of the true cause

of the damage. And that means that they are

often just tackling the symptoms. After many

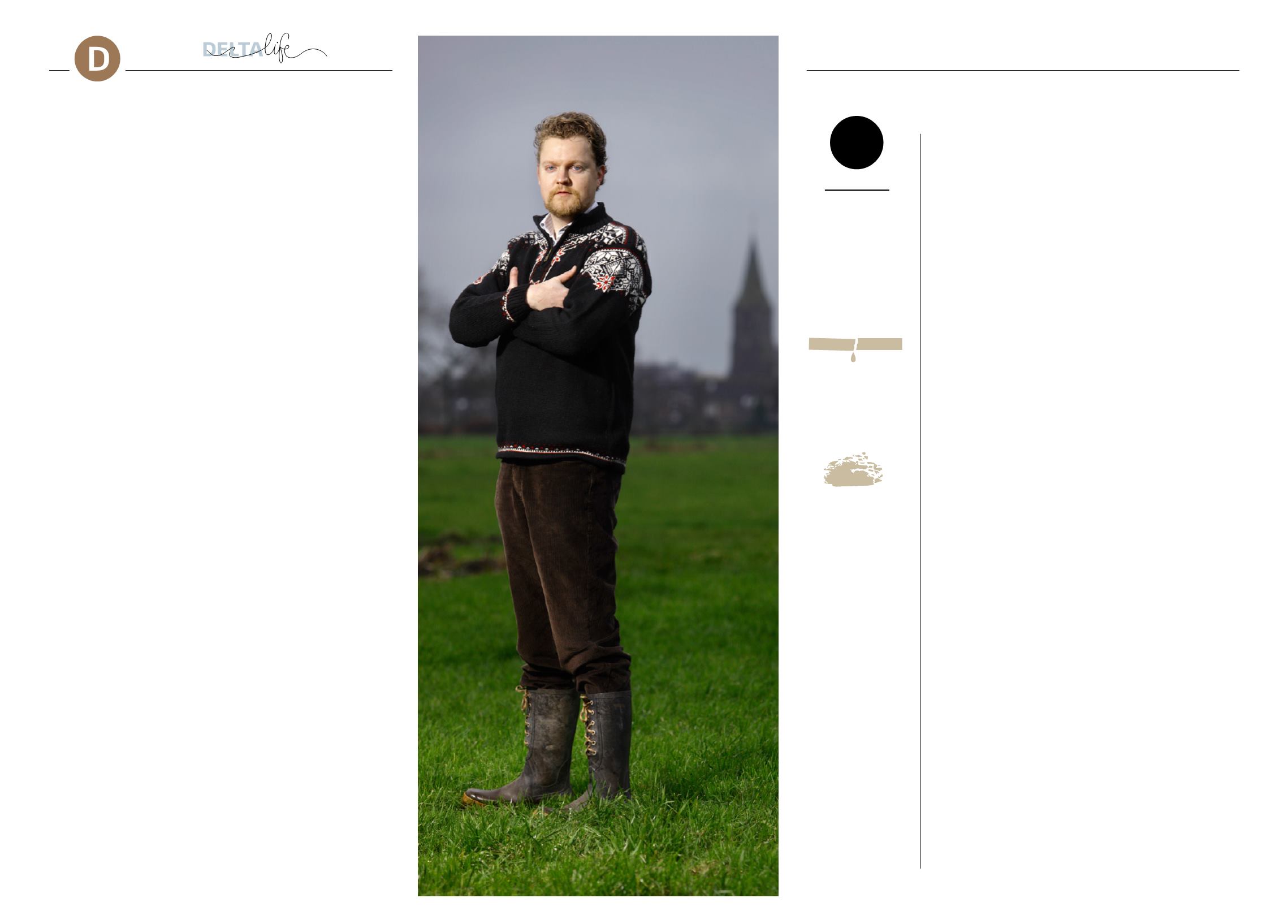

years of research, Gilles Erkens knows the true

cause – land subsidence – and, even more

importantly, the possible counter-measures.

T

hroughout the world, peat areas are popular places due

to their favourable location near the estuaries of major

rivers or because of the highly fertile soil. So peat areas

are used intensively for agriculture and other economic

activities, and also as places to live. Peat is rather

swampy, or ‘soft’, and so it has to be drained first.

In itself, the artificial lowering of the water table is a technique that

goes back centuries. However, we have only recently discovered how

much damage it can inflict. Draining the land, and building on it,

leads to a process in which the peat shrinks, oxidises and becomes

more compact. Land levels fall due to the resulting reduction in

volume. In time, the soil reaches the water table and draining is

needed again. The land-subsidence cycle starts over. ‘Once you

start pumping, you can’t stop; the land keeps on subsiding,’ explains

researcher and land-subsidence specialist Gilles Erkens.

We are also familiar with land subsidence during gas

extraction. Could it be that there are several types?

‘In broad terms, there are three causes of land subsidence associated

with human activities. The land can fall as a result of sustained

groundwater extraction. Mineral extraction is another possible

cause and, thirdly, it can also occur when peatlands are drained and

subjected to a load. Not enough people are aware of the third cause at

the moment. Because it can cause a great deal of damage, we want

people to become more aware of it and we would like it to have a more

prominent place on the agenda.’

What type of damage does land subsidence in peat

areas cause?

‘That varies. In the Netherlands, infrastructure is affected most, both

above and below the ground. The problem is that the land subsides,

but structures built on foundations don’t. That gradually results in

enormous levels of damage to buildings, roads, pavements and fencing.

Sewers, underground electricity networks and gas pipelines can break.

You can see howmunicipalities affected by this process need much

higher maintenance budgets than other municipalities or regions.

In the Netherlands, we have good water management and so flooding

is not a problem. But it certainly is in many other countries, where

peatland near the coast is drained for agriculture, leading to more and

more frequent flooding as the land subsides. If draining isn’t stopped,

flooding becomes semi-permanent, preventing the land being used.

For example, on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, entire stretches of

coast have become unusable due to draining for palm-oil plantations.

As a result, entire investments are – literally – under water.’

Do we know how high the costs are?

‘In the Netherlands, land subsidence costs every resident of the

country approximately €250 a year in additional maintenance.

Sewers, for example, have to be replaced twice as often as in

municipalities where the soil is not soft. That means less money for,

say, a swimming pool, sports or green facilities.

We still don’t know what the costs are internationally. But we believe

they are quite considerable. Better protection is needed for coastal

areas under threat, and then the costs for coastal defences and water

management can really mount up. Land that has already been lost to

the sea or that gets flooded regularly can’t be used and so it doesn’t

deliver any returns. And biodiversity is affected as habitats disappear.

An incidental effect of draining peatlands is that greenhouse gases are

released during the oxidation process. Recent studies have shown that

this effect puts a major burden on the atmosphere.’

Why is it still sodifficult toget the subject on theagenda?

‘Because the process is insidious, and people are not yet aware of it.

Many people in the Netherlands don’t even know they live on peat, or

that this involves extra costs for their house. And even quite recently,

it was still unclear that all these costs were linked to a single cause. In

the Netherlands, we have had land subsidence for a thousand years.

Government agencies have, so to speak, spent 995 years focusing

exclusively on keeping the water out. Fortunately, we are seeing a

change in the mood in the Netherlands, and local authorities and

parliament are tooling up. The Netherlands is leading the way in terms

of awareness-raising and counter-measures. We very much want to

use our lessons learnt at the international level. Precisely because

Land subsidence in

the Netherlands costs

approximately 250 euros

extra per resident for the

maintenance of housing

and infrastructure.

Sewers in regions with soft

soil have to be replaced

twice as often: once every

30 years instead of once

every 60 years.

The Greek island of Yali,

near Kos, is Europe’s

leading producer of

pumice stone, which is

used in foundations for

road construction on soft

delta soils. Pumice stone

is used to keep the roads

lighter and therefore to

reduce subsidence.

The coastal areas of

Indonesia and Malaysia

include 25 million hectares

of peat land, an area the

size of the United Kingdom.

Oxidising peat produces

greenhouse gases. After

the USA and China, Indo-

nesia is the world’s largest

producer of greenhouse

gases: more than 500

tons of CO

2

annually.

€250

CO

2

25million

hectares

DOSSIER

FACTS

‘THE HARDER

WE PUMP,

THE FASTER

WE FALL’

BY CARMEN BOERSMA

PHOTO: SAM RENTMEESTER